Pregnant Pause: To Have (or Not Have) a Baby on TV

Pregnancy made its first appearance on American TV in the 1948 sitcom Mary Kay and Johnny, bringing with it all those now-timeworn tropes that include the bumbling dad driving off to the hospital and leaving his wife in labor at home. Just a few years later, even the mere mention of the “p-word” on I Love Lucy—with the star comedian’s real-life pregnancy written into the script—was too controversial for CBS executives. She was “expecting.”

The tougher topic of abortion was invisible in television entertainment until 1972, when producer Norman Lear broke the rules once again, this time on his CBS series Maude. In a two-part episode the 47-year-old lead character, played by Bea Arthur, finds herself pregnant, and her soul-searching decision to have an abortion is treated without the usual laughs.

Today, the list of network, cable and streaming shows featuring recent TV storylines dealing with pregnancy, birth and abortion is a long one: black-ish, Girls, Shameless, East Los High, The Mindy Project, The Handmaid’s Tale, Call the Midwife, Scandal, Brockmire, Degrassi: Next Class, Jane the Virgin, BoJack Horseman, Glow, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and You’re the Worst, to name just a few.

More photos | Watch highlights of the panel | Exclusive interviews

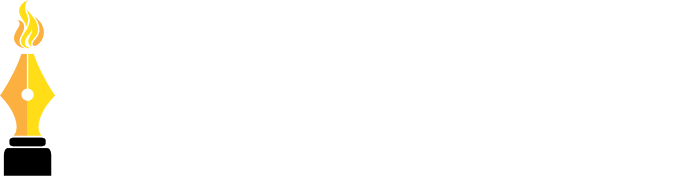

Hollywood, Health & Society’s panel on July 31 at the WGAW, “Pregnant Pause: To Have (or Not Have) a Baby on TV,” explored a range of topics on abortion, childbirth and maternal health. Featured speakers were Dr. Willie Parker, OB/GYN and author of Life’s Work: A Moral Argument for Choice; Justin Baldoni, co-star of the hit CW series Jane the Virgin; Sonja Perryman, manager of research and development at Wise Entertainment and associate producer of East Los High; Lizz Winstead, founder of the Lady Parts Justice League; Dr. Diana Ramos, OB/GYN and director for reproductive health at the L.A. County Public Health Department; Shadman Habibi, nurse-midwife, UCLA OB/GYN; and Gretchen Sisson, a research sociologist for Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) at UC San Francisco.

The panel couldn’t have been more topical—a woman’s right to choose is being challenged in many states; the number of C-sections has been increasing in the United States, where the percentage of surgical deliveries stands at 32% (the World Health Organization reports that the global healthcare community puts the ideal rate at between 10%-15%); the U.S. has the worst rate of maternal deaths in the developed world; and more women and their partners are exploring alternative birth options, including the use of midwives and doulas.

“I can’t help but wonder, if we start to look at the correlation between the disappearance of abortion care and our rising maternal mortality that we wouldn’t find a link,” Dr. Parker said.

Dr. Ramos pointed out that California is a bright spot in the overall bleak picture of the U.S. maternal mortality rate, a result of a decade-old state initiative called the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC). The CMQCC was founded at Stanford’s School of Medicine, and the organization’s website states that it “uses research, quality improvement toolkits, state-wide outreach collaboratives and its innovative Maternal Data Center to improve health outcomes for mothers and infants.” Current funders include the CDC and the California Health Care Foundation.

According to the World Health Organization, maternal mortality is defined as the death of a mother from complications while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of the pregnancy. In the U.S., that rate has soared. Between 2000 and 2014, maternal mortality increased 27 percent, from 19 per 100,000 to 24 per 100,000 (for African American women, Dr. Ramos said, it’s 40 per 100,000). The CDC Foundation estimates that 60% of these deaths are preventable.

In California, Dr. Ramos said, that rate is down to 7 per 100,000 (for African American women, it’s 26 per 100,000). Better than the national numbers, she said, but “still a lot of work to do.”

A look at the history of childbirth practices (Childbirth in America: Historical Perspectives) reports that at the beginning of the 20th century, most babies were born at home attended by midwives. By the 1920s, births began moving from the home into hospitals, and by the ’30s the number of births attended by midwives dropped to 15%. Less than 50 years later, 99% of births took place in hospitals attended by a physician. Today, Habibi said, the number of births attended by midwives has inched up to 3%.

Dr. Ramos attributed the overmedicalization of childbirth (including the rising rate of C-sections performed) to one major factor: Women are waiting longer to have babies, and older mothers mean more complications.

“A lot of the moms we’re getting are 35 and older,” she said, which increases risk for health problems such as preeclampsia (pregnancy-induced high blood pressure, which can be fatal). Fortunately, in the U.S., she said, “we have the amazing ability to intervene [medically] when necessary.”

California is a bright spot in the overall bleak picture of the U.S. maternal mortality rate, a result of a decade-old state initiative called the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC).

Dr. Parker, one of the few remaining abortion providers in Alabama, was raised in a Christian household in Birmingham, and converted to an even more fundamentalist form of Christianity as a young man. Trained as an OB/GYN, he believed that his faith precluded any possibility of providing abortions to women, but he eventually became an outspoken “reproductive justice advocate.” In 2009, he stopped practicing obstetrics to focus entirely on providing safe abortions.

His personal transformation, although radical, took some time. As an obstetrician, Dr. Parker’s first job out of residency was “catching babies” in hardscrabble farming communities around Merced, in California’s Central Valley. “I saw women with unplanned, unwanted or wanted but lethally flawed pregnancies,” he said. “But I couldn’t reconcile being Christian and providing abortions.”

After 12 years, the battle between his core Christian identity and the unspoken, dire need that he saw in the faces of the women he cared for finally reached a crisis point. One day, he was listening to a recording of the “Mountaintop” sermon by Martin Luther King Jr., in which Dr. King spoke about the parable of the Good Samaritan. Dr. Parker saw the fallen traveler in need on the side of the road as a stand-in for his poor patients—most of them women of color.

“I ultimately decided it was no longer satisfying to default to traditional thinking that Christianity was mutually exclusive with being an abortion provider,” Dr. Parker told the audience.

Sisson’s research at ANSIRH focuses on television’s depictions of abortion “not only … as a healthcare and policy issue, but also in how it operates in cultural conversations and narratives.”

The last five years, she said, has brought rapid change when it comes to abortion on TV—changes that include an increase in the number of depictions and more diverse characters having abortions.

If one looked at TV entertainment over the last 25 years—once replete with storyline tropes such as the “convenient miscarriage” that would end an unwanted pregnancy, or the woman’s last-minute change-of-heart while she sits inside the health clinic—those characters who did have abortions used to be predominately white, Sisson said. “But then Shonda Rhimes came along and changed that, almost single-handedly.”

Sisson added that the depictions of women changing their minds at the last minute were particularly misplaced. “That’s not how most women go about making their decision,” she said. “Ninety-five percent of women who go to clinics to have an abortion feel very confident about their decision and don’t have any hesitation.”

Beyond race and ethnicity, she added, the age of a TV character getting an abortion has also changed.

“More mothers are getting abortions—that’s been a big shift,” Sisson said.

What part could TV play in the fight for women’s reproductive rights and other topics related to childbrith?

“The media has a very important role to play,” Dr. Parker said. “But they’re morally neutral and do a disservice to the public when they create false equivalencies and try to strike a balance between pro-life and pro-choice narrative. They’re validating opinions not based in fact.”

Baldoni, an actor, director and filmmaker, recounted wife Emily’s home birth of their daughter, Maiya Grace.

“When my wife got pregnant I didn’t even think about the home birth option until she brought it up,” said Baldoni, who now describes himself as a passionate advocate.

He called that momentous day—complete with midwife, doula, music and prayer— “one of the most beautiful, spiritual and calm experiences ever.”

“I got a chance to be there for my wife, sharing an experience—just me and my wife and my daughter—that would have never been possible in a hospital,” he said. But he added that there’s a lack of education on home births being an option, and that’s where TV can play a role.

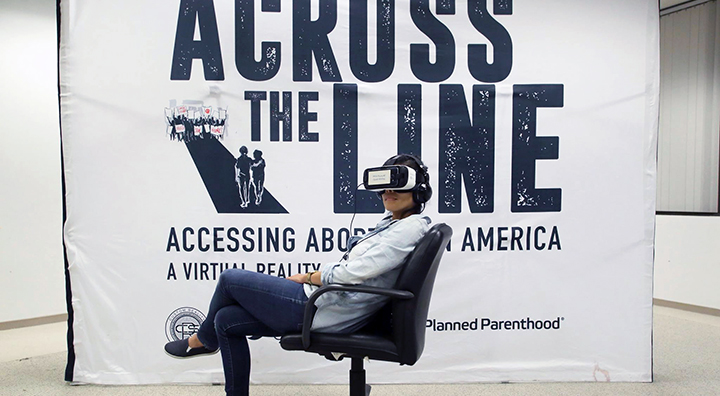

The event’s reception featured “Across the Line,” a virtual reality experience that combines 360° video, CGI and actual audio and documentary footage of the types of bullying and harassment that sometimes occurs outside a health center providing safe and legal abortion. The seven-minute film, produced by Planned Parenthood and created by Nonny de la Peña’s Emblematic Group and CRS Productions, powerfully depicts the typical entry to a clinic for providers, staff and patients.

For more information about the experience, visit AcrosstheLineVR.org.

This post was updated on 08/13/17.