“Care Circles: It Takes a (TV) Network”

WGAW

“Who here has either been a caregiver, or received care?”

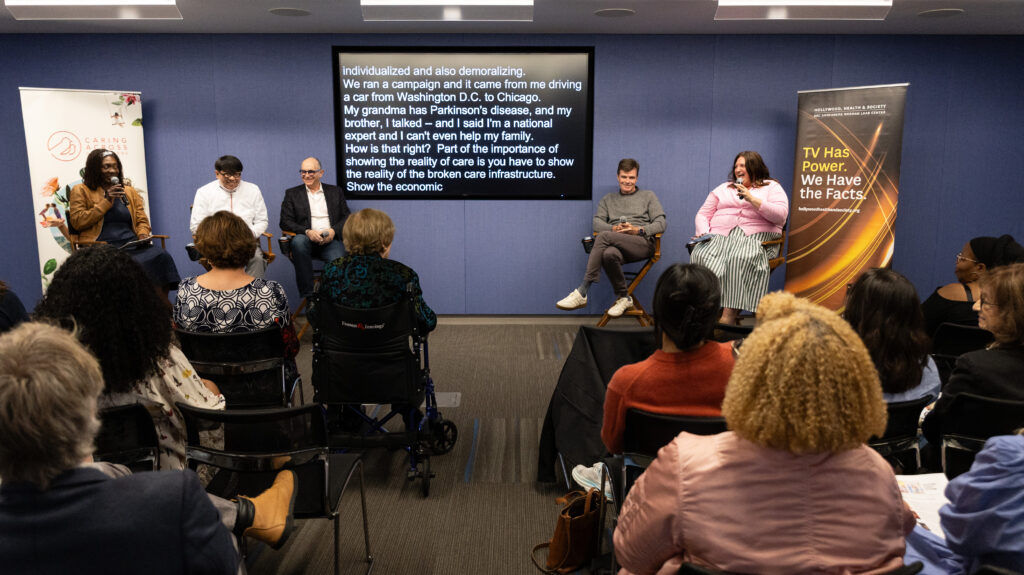

asked Keisha Zollar, disabled writer, comedian, mom, and writer for Dying for Sex, the hit Hulu series. Everyone in the room raised their hands. “Okay, good. I was about to be nervous…the reality is that care is in all of our lives.” As moderator of a panel about caregiving, Zollar opened the discussion by asking, “Why do you care about care?”

Featured speakers included Dr. Joe Sachs, executive producer/writer of The Pitt (HBO Max), Morgan Sackett, executive producer/director A Man on the Inside (Netflix), care worker Allen Galeon, and Nicole Jorwic, chief program officer, Caring Across Generations, which co-sponsored the event with Hollywood, Health & Society and the National Domestic Workers Alliance, on June 11 at the Writers Guild of America, West. They shared moving scenarios and thoughtful insights that illustrated the importance of community, connection and human servicesfrom homes to hospitals to retirement facilities.

Morgan Sackett, spoke of the documentary The Mole Agent by Chilean filmmaker Maite Alberdi, as the inspiration for A Man on the Inside. He also personally connected with the story, watching the toll that caring for his father took on his mother, an accomplished judge, and then sadly witnessing her decline. Inspired by the patience of the team caring for residents in her memory care home with dignity, ‘we felt we should tell that kind of story—and also make some jokes.”

Joe Sachs, also an emergency physician, referred to working with an “angel,” whose care for patients informed the social worker character on The Pitt. He quoted Dr. Francis W. Peabody from a speech to Harvard medical students 99 years ago: “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is the interest in humanity. The secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” Joe related, “What we try to convey in the stories we tell is that everyone is worthy and deserving of care, even in a healthcare system that is broken and failing.”

“When you see care portrayed on screen, you see your own perspective and realize that you’renot alone. It’s a common experience,” said Nicole Jorwich. While fighting on in D.C. for policies that ensure access and funding for home care that meets people’s needs, she also has a connection to caregiving with a 35-year-old brother with autism whom she cares for as well as her grandparents. “You can’t think about care going only in one direction.”

Allen Galeon is a full-time professional care worker. “I’m pretty sure 100 percent of us relate to the fact that caring for someone is a challenging task.” It involves asking for lots of favors from babysitting to transportation. With a wide smile, he introduced his ‘consumer’ in the first row of the audience with her adult daughter, adding he also cares for his own mother and son. “It’s a life of serving.” He described his day “about connecting myself to my community as the systems navigator from waking up until evening.”

Keisha addressed storylines in each show that dramatized caregiving, as seen in clips at the beginning of the event introduced by Kate Folb, director of Hollywood, Health & Society. In The Pitt, an empathetic doctor with experience caring for her autistic sister, warns about caregiver’s fatigue as a woman faces additional duties after her mom breaks an arm. “We start with the dramatic needs of the characters and amplify their own emotional journey,” explained Sachs. The social worker then offers free resources including companionship and meal delivery to help givethe daughter a much-needed break.

A Man on the Inside changed a lot of preconceptions about how we see senior living retirement homes portrayed, suggested Keisha. Morgan hopes the series shines some light on loneliness.“It’s easy to get isolated when caring for a spouse as your focus every day.” His mother-in-law had canceled trips to California five times after her husband died. When she watched the series, she planned a visit. Morgan explained the show wants to ask questions—and to entertain. “People are wise in their 70s and 80s, and 90s—and hilarious.”

Keisha asked her fellow storytellers what tropes they’d like to see changed in caregiving portrayals, offering “I see a lot of people north of 65 shown as disabled and dour, who we should pity. We minimize everybody’s humanity.” Morgan agreed, “Older people are shown as grumpy and a burden. They’re really amazing. If you got to be 80, you won.”

Some claim that The Pitt is ‘compassion porn,’ Joe added, describing a storyline about an older patient with dementia: “He’d invented CPR.” Based on the historical blueprint of the 911 system, this character trained unemployed Black youth to be paramedics in the poorest part of Pittsburgh where people weren’t receiving emergency health care. It’s a little-known and important story of how this man saved underserved lives in the 1970s.

Caregiving takes a village, but it’s not usually seen on TV. Lydia Storie, director of Culture Change for Caring Across Generations, explained there are 5 million residents in care right now, and its recent study found that only 10 percent of television series include a caregiving storyline.

But scenes from the shows modeled powerful portrayals of care circles. They can be dynamicand complex, a collective effort shared with family, friends, care workers, and support programstold authentically about caregiving for the aging, children, and people with disabilities. Nicolesaid, “It’s the work that makes other’s work possible.”

Care workers are predominantly women of color and immigrants, noted Rachel Birnbaum, who works with nannies and healthcare workers. Though devalued in society as unskilled labor and left out of labor protections, she explained, ‘they take care of what’s most important to us, which is our homes and our families.”

Allen agreed that caregivers are often misrepresented. “I believe that all of us are gifted with an unlimited capacity to care for someone.”