Atomic Football: The Nuclear Playbook in a Strange New Era

Hollywood, Health & Society’s panel “Atomic Football: The Nuclear Playbook in a Strange New Era” was a night to think about the unthinkable: nuclear proliferation and war, near-catastrophic errors when it comes to keeping arsenals secure, the use of cyber attacks and the grim prospect of terrorists getting their hands on a weapon of mass destruction.

But there was also a ray of hope breaking through all the visions of mushroom clouds, and that is the role entertainment can play in raising public awareness and concern.

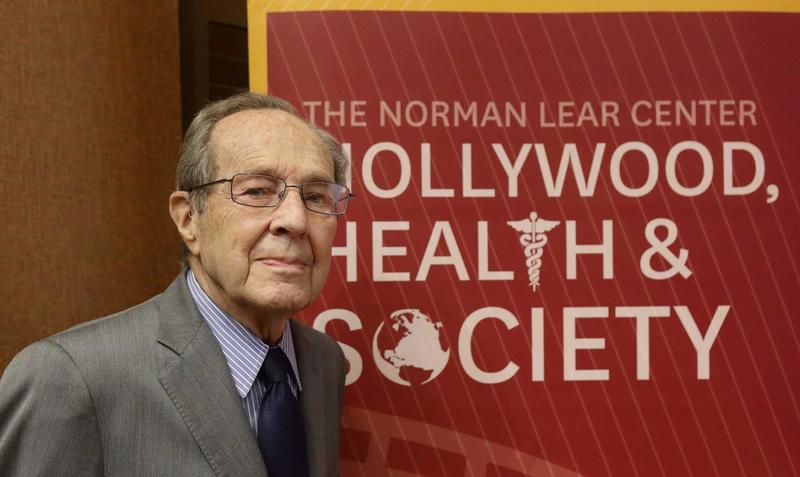

The event featured special guest speakers William J. Perry, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and former U.S. Secretary of Defense; Valerie Plame, former covert operations officer for the CIA who worked in nuclear counter-proliferation, and author of Fair Game: My Life as a Spy, My Betrayal by the White House; Barbara Hall, creator/executive producer of Madam Secretary (CBS); David Grae, executive producer of Madam Secretary; Eric Schlosser, an investigative journalist and the author of Command and Control; and Eric Chien, technical director of Symantec’s Security Technology and Response Division.

More photos | Watch videos from event

Clearly, the main reason that the audience, which included actor Sean Penn, braved brisk temperatures to come out on a weeknight to attend the event—held Wednesday, Jan. 25 at the Garland Hotel theater in North Hollywood—was the high-wattage panel, a combination of nuclear security experts (Perry, Plame and Schlosser), television industry leaders (Hall and Grae) and Chien, a Santa Monica-based cyber security expert credited with helping to uncover Stuxnet, a destructive piece of malware that’s been called the world’s “first digital weapon.” Chien indicated that when it came to cyber attacks and electronic hacking, email accounts were the least of our worries.

Of course, if anyone could convey the sheer gravity of the topic it’s Perry, a veteran Cold War warrior hailed by Politico as “America’s nuclear conscience” in a recent article. And what he had to say on this night set off some alarms.

“We’re at greater risk than during the Cold War,” he said, adding that a new nuclear arms race has already begun given President Trump’s recent remarks in a tweet that “the United States must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability.” In a phone call a day later with a morning TV show, Trump said: “Let it be an arms race.”

What really keeps Perry up at night, though, is the probability of a terrorist group detonating a nuclear weapon in an American city like Washington, D.C., effectively crippling our government and setting off a cascading series of economic, political and social crises throughout the U.S.

On a similar note, Plame worries chiefly about Pakistan, a nuclear power whose system that safeguards its weapons arsenal, according to Plame and others, has been compromised, and the country’s security services infiltrated by those hostile to U.S. and Western interests.

Plame’s story about how Pakistan developed its nuclear weapon capability could have been ripped straight from a Madam Secretary episode. After its defeat in a war with arch-enemy India in 1971, Pakistan embarked on a nuclear weapons program with help from A.Q. Khan, a German-trained metallurgist who used a secret network to get around international laws to obtain materials and technology for enriching uranium. In 1998, Pakistan successfully tested its “Islamic bomb,” declared itself a nuclear power and remains one of three nations (along with India and Israel) outside the the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Plame said that Khan later sold nuclear technology and expertise to North Korea and Iran before the CIA penetrated his black-market network (a former colleague of hers named Mad Dog recruited one of Khan’s partners by chatting him up in a bar in Dubai) and brought it down. Today, she said, much of the nuclear material remains unaccounted for.

“Americans just think that this whole nuclear threat has gone away, when in fact it’s more dire than ever,” Plame said. “Where do we begin to make a difference? That will be the challenge.”

She credited N Square, a collaborative initiative of the Ploughshares Fund, with re-framing that challenge in new, innovative ways to raise both public awareness and concern.

On its website, N Square calls for “a new national dialogue about nuclear disarmament that helps bring the nuclear weapons issue back into public consciousness. . . . Our overarching goal is for more citizens throughout the world to see themselves as architects of a future free from nuclear risk.”

At one point during the evening, Perry and Schlosser sat on stage in friendly conversation, with Schlosser quietly drawing out the 89-year-old Perry’s sometimes stark experiences during his long career in national security.

He first became involved with nuclear weapons during the Cuban missile crisis, a 13-day confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union in 1962 that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. Perry then was a young member of a small team that sifted and analyzed daily intel to present to President Kennedy. Perry said each day’s analysis of the crisis convinced him that it was going to be his last day on Earth.

One hitherto but crucial storyline emerged as Perry spoke about near-misses. In several instances, the world came close to blundering into nuclear war only to be pulled back from the brink through luck and the cool, rational decisions of low-level players.

“I don’t feel apocalyptic, I don’t have a desire to depress people. These things are preventable [but] what’s needed is public awareness.”—investigative journalist Eric Schlosser

During the Cuban crisis, a Russian submarine escorting supply ships to Cuba came under attack by an American destroyer using depth charges to force it to surface. The sub was equipped with tactical nuclear torpedos (unknown to the U.S. command at the time), and the captain had been authorized to use them if attacked, which was his intention. Such a strike on an American vessel, Perry said, would have certainly escalated into a widespread nuclear war. But the sub’s torpedo launch required a unanimous vote by three of the ship’s officers; one of them said nyet.

Another example falls into the category of false alarm. In 1979, years after the Cuban showdown, Perry was serving as undersecretary of defense for research and engineering under President Jimmy Carter when he received a “heart-stopping” phone call at 3 a.m. from a watch officer at the North American Aerospace and Defense Command (NORAD), saying his computer was showing that 200 Soviet nuclear missiles had been fired at the U.S. In that critical situation, under the “launch on warning” policy, the president normally would have been told immediately, giving him a five- to six-minute window to fire American ICBMs. Instead, the watch commander chose to wake Perry, and told him that he was certain his computer warning was a false signal. Later, they discovered that during the change in watch, a NORAD operator had mistakenly inserted a training tape into the computer that simulated a nuclear attack.

“Happily, the general [on watch] that night was sober, careful and experienced,” Perry said. “And he thought it through and said, ‘This doesn’t look right.’ ”

Madam Secretary, which centers on Secretary of State Elizabeth McCord (Téa Leoni) as she navigates the show’s mix of Washington politics and foreign policy intrigue, has aired several storylines about the nuclear threat. “It’s been in the fabric of our show from the beginning,” Grae said.

“When you’re doing a TV show you want to raise the stakes of the drama, and there are no higher stakes than nuclear issues,” Hall said. “Part of what we do on the show is to entertain people, but give them a civics lesson at the same time.”

Although she described the show’s drama as “heightened reality,” Hall said the writers are careful not to cross the line where [the audience] begins to think that it’s fictional.

“We want to be truthful about depicting what the state of the world is, in particular where nuclear issues are concerned,” she said. “We have an ethical obligation to root our show in reality so people are aware that what we’re talking about is an actual threat.”

Hall said a Madam Secretary episode even managed to get in a reference about the so-called Doomsday Clock, an internationally recognized symbol of how close we are to destroying civilization through nuclear weapons, climate change, bioweapons and cybertechnology—with midnight being the hour of destruction. Each year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists considers such factors as recent comments on nuclear arms by political leaders, a growing disregard for scientific expertise and a global rise in nationalism in making its calculation.

For Schlosser, research for his 2013 book, Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident and the Illusion of Safety, sparked a 10-year investigation covering nuclear weapons issues, in which he came across so many accidents and near-misses and problems in the control of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. His nightmare scenario? A rogue state or group using cyber warfare to hack into our nuclear system and create a false alarm, effectively “spoofing” the U.S. into launching a missile. Listening to him, members of the audience probably had to keep reminding themselves that this was not in the realm of science fiction, or part of a technology-gone-awry plot from one of several TV and film clips shown during the panel (Fail Safe, anyone?)

That scenario, as Chien seemed to indicate, was not so far-fetched. “Stuxnet opened up a Pandora’s box,” he said.

Developed by the U.S. and Israel as a way to attack and destroy an Iranian nuclear centrifuge facilty, Chien said that Stuxnet signified a major leap in the evolution of cyber attacks being used by nation-states to inflict harm.

At one point in the evening, Schlosser perhaps sensed that the audience might have needed a respite from the doom-and-gloom before eventually heading back out into the chilly night and the drive home.

“I don’t feel apocalyptic, I don’t have a desire to depress people,” he said. “These things are preventable [but] what’s needed is public awareness.”

With a nod to the writers and producers in attendance, Schlosser said: “You can’t minimize the impact that popular culture can have on these very important issues.”

He credited the 1983 TV movie “The Day After,” about the aftermath of a nuclear strike on the U.S., with raising public awareness.

The film was watched at the White House by President Reagan, Schlosser said, and it played a real role in persuading Reagan, who had been a nuclear hawk, to work toward abolishing these weapons. Reagan held a summit with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, but the two sides couldn’t reach an agreement then.

Today, there are roughly 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world possessed by nine nations. The U.S. and Russia, which account for 93% of them, and the other countries still rely on an outdated 20th century doctrine known as mutually assured destruction to keep the nuclear peace.

The morning after the “Atomic Football” event, the Doomsday Clock was moved to its closest time to the apocalypse in 64 years. It now stands at 2 minutes and 30 seconds to midnight. ◼︎

This post was updated on 02/07/17.