Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World

In 1946, The New Yorker magazine devoted its entire August 31 issue to John Hersey’s 31,000-word essay on the effects of the atomic blast on the people of Hiroshima one year earlier.

In vivid reporting, Hersey, then a young war correspondent, details the lives of six survivors—or hibakusha—of the bombing. He writes:

“A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors. They still wonder why they lived when so many others died. Each of them counts many small items of chance or volition—a step taken in time, a decision to go indoors, catching one streetcar instead of the next—that spared him. And now each knows that in the act of survival he lived a dozen lives and saw more death than he ever thought he would see. At the time, none of them knew anything.”

In the days and weeks following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, the U.S. government and military waged a campaign of suppressing information about the devastating toll that the attacks inflicted.

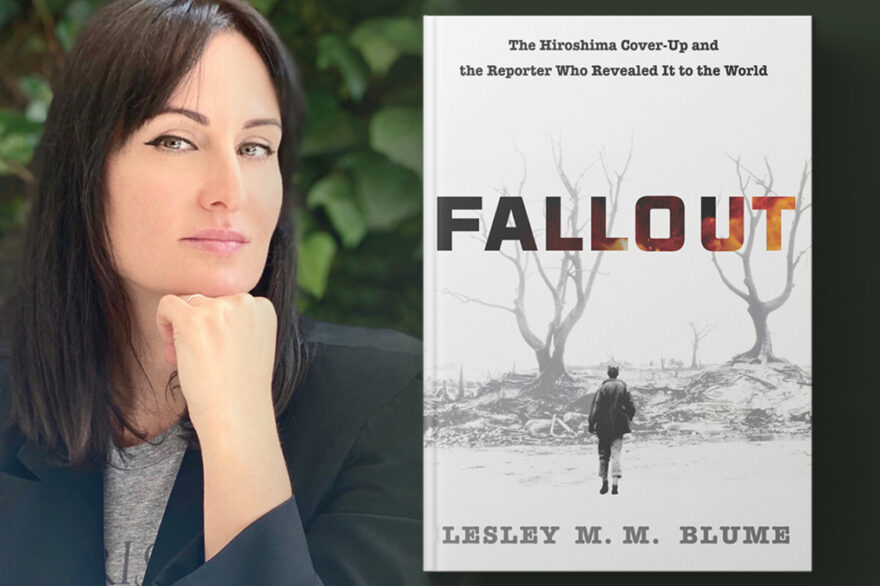

How Hersey got the story and delivered a landmark work of journalism is itself the subject of Lesley M.M. Blume’s new book, Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World. Blume, joined by investigative journalist Eric Schlosser, discussed her book as part of an online panel discussion presented by Hollywood, Health & Society on Thursday, Sept. 30.

Blume, a Los Angeles-based journalist, author, and biographer, has had her work appear in Vanity Fair, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Her book Everybody Behaves Badly was a non-fiction New York Times bestseller. Schlosser, an author and investigative journalist, has written books that include Fast Food Nation; Reefer Madness; and Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, which was a finalist for a 2014 Pulitzer Prize.

Blume said that before writing Fallout, she wanted to drive home the importance of investigative journalism and a free press, which she believes is under attack. She found a way through Hersey’s reporting on Hiroshima—which Schlosser called the “greatest non-fiction” piece of writing.

“Hiroshima has the strange distinction of being one of the most covered stories, and one of the most covered up,” Blume said in an interview that’s posted on YouTube.

Although Hersey attended Yale and Cambridge, Blume said, he grew up poor as the child of missionaries in China, and saw himself as an outsider—yet with access to the privileged centers of power in New York and Washington, D.C.

“Being this outside observer was an enormous advantage when it came time to report on Hiroshima,” Blume said.

Schlosser said that despite the subject matter, Hiroshima is, in a way, uplifting and hopeful—a story about the survival of the human spirit under the worst possible circumstances.

“I read it for the first time maybe 30 years ago,” Schlosser said. “I’ve read it three or four times since then. The story it tells and the subject it addresses could not be more important.”

Before embarking on the journey that resulted in Hiroshima, Hersey and his editor at The New Yorker, Wallace Shawn, agreed that coverage of the bombing was incomplete and shrouded in secrecy. Most of the reporting at the time centered on the power of the bomb and its destructive force on buildings. Both in Washington and in Tokyo, U.S. officials tried to contain and spin the story of the aftermath of the blast, playing down the impact of radiation—even going so far as to announce that the city of Hiroshima and surroundings were radiation-free.

In covering the world conflict in both Europe and the Pacific, Hersey had seen how dehumanization enabled the worst acts of the war. With Hiroshima, he and Shawn now decided that it was time to put faces to the staggering number of casualties.

When Hersey entered Japan in May 1946, Blume said, the country was essentially in total lockdown under Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who commanded the allied occupation of post-war Japan. Hersey was a well-known and celebrated war correspondent and author—he had won a Pulitzer Prize in Fiction in 1945 for his novel A Bell for Adano—and had profiled MacArthur in his book Men on Bataan, published in 1942. By the time Hersey arrived in Tokyo, the bombing of Hiroshima was being seen as old news by both the U.S. military and by many of Hersey’s fellow war correspondents. He was granted permission to visit the city for two weeks.

The rest, as they say, is history.