What’s So Funny About Climate Change?

What do you get when you mix TV legend Norman Lear with climate change experts and some of the funniest comedy writers around, and put them all in front of a packed house?

Punchline aside, the result was actually an energetic, sharp panel discussion titled “What’s So Funny About Climate Change?” that sometimes did get a bit boisterous—these were comedy writers and performers, after all—as it set out to answer this question: If global warming is such serious business, why do TV comedians get it right, covering the issue better—and more often—than films, dramatic series and even the nightly news? Is doom and gloom best served with a dose of humor?

More photos | Watch video highlights of the panel | Read transcript

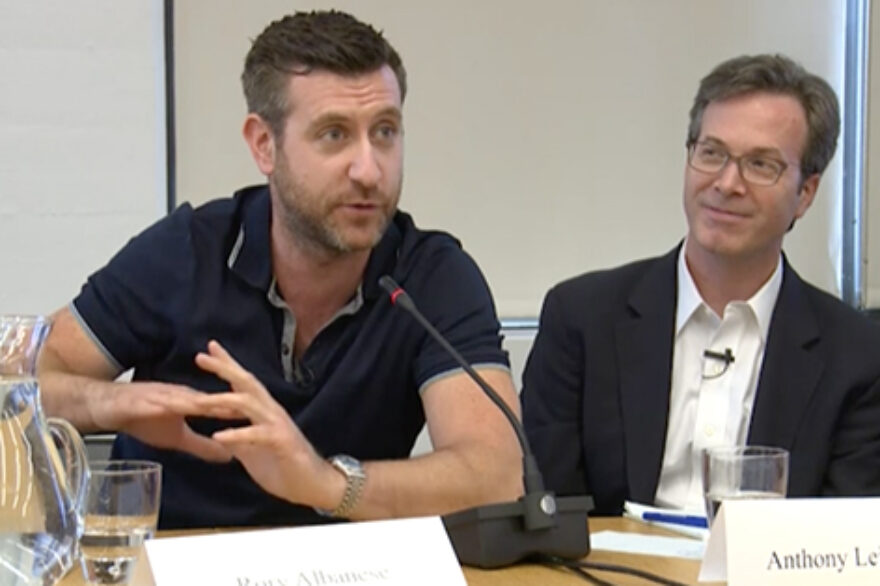

In addition to Norman Lear, the Sept. 19 panel—presented by Hollywood, Health & Society (HH&S) and co-sponsored by the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE)—featured Rory Albanese, showrunner for The Minority Report With Larry Wilmore and former showrunner, The Daily Show With Jon Stewart; Chris Albers, writer for Borgia and writer/producer, Late Night, The Tonight Show With Conan O’Brien, and Late Show With David Letterman; Sidney Harris, science cartoonist for The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal and other publications; Lyn Lear, environmental activist and producer; Anthony Leiserowitz, Ph.D., of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication; and Lizz Winstead, co-creator and former head writer of The Daily Show and author of Lizz Free or Die: Essays. It was held at the WGAE in New York.

Serving as co-moderators for the panel were Michael Winship, senior writer, Moyers & Company, and president of the WGAE; and Marty Kaplan, director of the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center.

Outside, the city prepared for a week of climate-related activities that would include an estimated 400,000 participants in the People’s Climate March and the UN Climate Summit 2014, where political leaders gathered to set a framework for addressing the most daunting environmental issue facing the planet. Perhaps they could have taken some cues from the panelists. Although they wrote comedy for a living, there was also some meat on their funny bones.

“We hope today’s discussion will inform and inspire you to address this extremely critical issue in your work,” HH&S Director Kate Folb said in welcoming the full house, which included TV writers/producers from shows including The Good Wife, Nurse Jackie, SNL, South Park, Two & a Half Men, Drop Dead Diva, Supernatural, NOVA, Tyler Perry’s House of Payne and Days of Our Lives.

Kaplan noted that the organizers for the people’s march, scheduled for two days after the HH&S event, were planning a moment of silence at the beginning followed by an outpouring of cacophony.

“Well, we are the cacophony,” he noted, gesturing around the room.

When Kaplan asked why comedy seemed to have the chutzpah to say what other media won’t (a question taken right from the panel’s subtitle), it was up to Lear—whose ground-breaking hit shows All In the Family, The Jeffersons and Maude, to name just a few, first brought social issues to TV screens more than four decades ago—to get the ball rolling.

Marty Kaplan, director of The Norman Lear Center, noted that the organizers for the people’s march, scheduled for two days after the HH&S event, were planning a moment of silence at the beginning followed by an outpouring of cacophony. “Well, we are the cacophony,” he noted, gesturing around the room.

Lear said that when he was starting out, TV executives and studio heads were wary of discussing big social issues, pointing out that America’s entertainment landscape was filled with sitcoms such as The Beverly Hillbillies and Green Acres, with storylines like “the roast is ruined and the boss is coming for dinner.”

“I was told if you want to send messages, use Western Union,” Lear said. “Before All In the Family, TV families had no real problems. Today, we just hear bumper sticker arguments on television, but they don’t give us any context.”

“Climate change has become a political issue,” Albanese said. “People pick a side. The left likes the environment. Therefore the right has to hate it. We give everyone an equal platform as if it’s worthy of debate. The Earth is in trouble. There’s really not a counter argument. So you get people on one side who think hurricanes are caused by gay marriage.”

“We’re cursed with reason,” said Lear, who added that a little more anger probably wouldn’t hurt when countering climate-deniers.

But his wife, Lyn Davis Lear, a producer and veteran environmental activist, told the audience how she struck a balance—a mix of concern and optimism—in trying to sway minds with the short film that she produced, What’s Possible, for the opening ceremony of the UN Climate Summit 2014. It’s using “emotion and a sense of the spiritual,” she said. “You have to reach people with how climate change affects their everyday lives.” A teaser of her film, directed by Louie Schwartzberg and featuring the voice of actor Morgan Freeman, was played for the panelists and audience.

Lyn Lear said that leaders in the climate movement have sensed that a tipping point has been reached. “With clean forms of energy more competitive with fossil fuels, there’s a sense that things are turning around,” she said.

“Hope is a critical emotion in reaching people about climate change,” said Leiserowitz, an expert in climate change communication. But he admitted that “you couldn’t design a problem that’s a worse fit” for getting people to take on a sense of urgency.

“This is an issue that’s invisible,” he said, referring to the unseen CO2 that pours out of car tailpipes and smokestacks.

He said that TV networks’ belief that they would lose viewers over coverage of global warming was misguided. “The other side is a small minority that has intimidated the country into not talking about the issue,” Leiserowitz said. “Six Americas,” a study conducted by the Yale Project, demonstrates that only 15 percent of Americans are dismissive of climate change. The report found that a majority of people are alarmed, concerned or cautious, he said.

“People want to know more,” he said, and viewers who are engaged tend to seek out more information. Calling it a “gateway drug,” Leiserowitz said that comedy is uniquely suited to conveying the message about global warming. “We come back because we love to laugh,” he said.

But Albers, who also spoke about climate change from a personal standpoint—his home in New Jersey was badly damaged by Superstorm Sandy—said comedians and comedy writers can’t do it alone. “We need a story that we can respond to,” he said. “Our shows respond to the news. If the news isn’t talking about the issue, it’s more forced if we bring it up.”

Speaking truth under the guise of entertainment and jokes is nothing new to comedy writers and performers—court jesters were doing it in the medieval ages.

“Comedians have become trusted,” Winstead said. “People believe they’re truthful and don’t have an agenda—other than finding a common enemy and then pointing up the hypocrisy.”

“It can’t just be the comedy shows and a couple hosts on MSNBC who are carrying the water,” she added. “We need better messaging.”